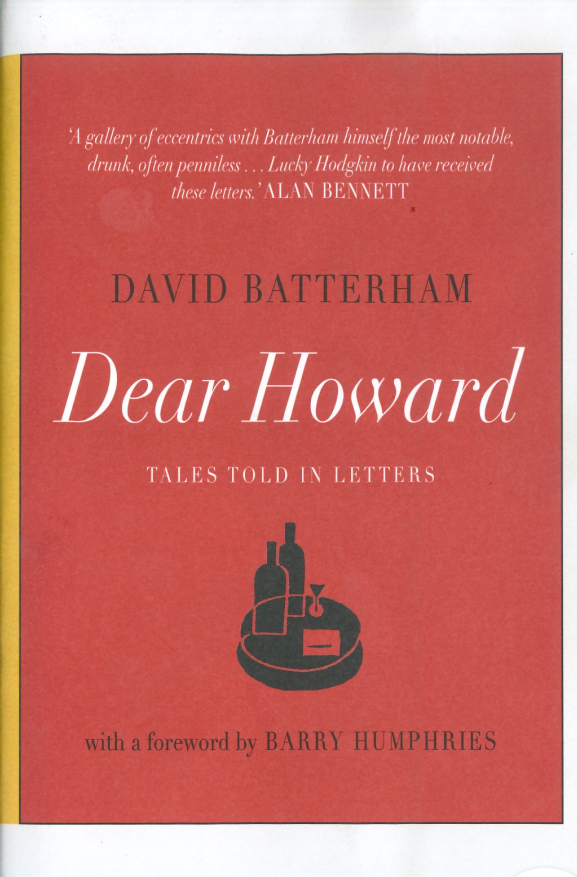

David Batterham – Dear Howard: Tales Told in Letters

Never was there an apter book for a blog about books than a book by a book dealer. Even aptlier, it was found behind my bookshelves, just a few days ago. I have no idea how it got there, nor who gave it to me: I certainly didn’t buy it. But if Dear Howard tells us anything, it’s that provenance is always a misty business, and who knows where the thing will end up? David Batterham’s decades of letters to his friend, the painter Howard Hodgkin, never received a reply, but then they weren’t written in the spirit of pure correspondence. Batterham diagnoses himself as “a bit like an alcoholic about my letter-writing. I sneak off with my pad and binge a few pages, blanking out the real world and its problems.”

And certainly the world of book-dealing seems, if not unreal, at least unrecognizable to our humdrum lives. Batterham’s peers flounce in and out of the letters: one, “more irritating and successful every visit, has installed a pallid linguist who now conducts all conversations, though I am still allowed to shake his hand.” But if many of his contacts are necessary evils, some become dear and longstanding friends. A letter from Paris in 1990 touches on Charlotte and Jacques, who has just sold four Old Master sketches to the Louvre for 200,000 francs.

On my last visit we had been discussing whether collecting is an obsession, as Charlotte suspected, or a passion as Jacques insisted. Charlotte was very cheered when I said he seemed to have become more obsessive about his passion. Jacques just beamed and clearly thinks he’s more passionate than ever.

By this point, 200,000 francs bats no eyelids. We have long since learned that in the book trade, at least at this level, it’s some pretty handsome sums that change hands, then slip straight through the fingers. In May 1974, Batterham writes that “my overdraft has increased during the last eighteen months from ₤3,000 to ₤18,000. This ₤15,000 doesn’t seem to be on my shelves.” By 1987 he has got this down to ten grand, “but still [has] no stock to speak of.”

The money that Batterham spends on stock, wine and the odd trader-wooing blow-out, he saves on accommodation. The letters give off a shabby, Bohemian glamour, a sort of Graham Greenery with the due jet-setting – his raids include Texas, Tunisia, Venice, Istanbul, etc. – and the mildly vicious streak. In Texas he bumps into “a huge bald slob,” and in Barcelona “a fascinating Jewish gnome” by the scarcely credible name of Edmund X. Kapp (“his chief claim to renown seems to be that he is the only person for whom Picasso actually sat for a portrait”).

Indeed, Batterham is never far from greatness, or rather from the great and the good. We learn that he counted the late Prince Philip among his clientele for a while – “a good customer”, apparently, if an atypical one. “The Duke keeps a cupboard of goodies, such as the books he buys from me, so that people who want to give him a present can choose something he is known to like! They then buy it from him and give it back.” Perhaps we should not be surprised to learn that Batterham specialises “in books one can enjoy without having to read”: the kings of the coffee table, like Edward Lear reprints or Les Meilleurs Blés, “a seed catalogue with coloured lithographs of ears of corn.” Bibliomania takes many forms, and despite the presence of “no poetry, history or literature,” the reader rests assured of some heavy-duty, lightly-worn culture on Batterham’s part. None of which matters as much as the prose, which rarely strays or falters.

It might be that, like Plato, Batterham fights shy of Literature because it represents his great temptation. “I may be ‘in denial’ over my childhood ambition to be either a Tramp or an Author, or even both,” he admits. In a letter dated 3rd January 2000, he reports that he and his wife Val had a tryst with the Heaneys, Seamus and Marie, at Thomas Hardy’s childhood church on New Year’s Eve. They were there for the turn of the twenty-first century, right where Hardy himself had seen the turn of the twentieth. The party “huddled under a yew tree” to shelter from the pouring rain, while Seamus read “The Darkling Thrush”, Hardy’s great vigil poem on “The Century’s corpse”. If you and I had been party to that, profit and loss would likely have been far from our thoughts, too.

Dear Howard is published by Redstone Press and is available here.