This is just to say

Thank you to everyone who has taken the time to follow this blog over the years. I wish that the articles had come thicker and faster. You can now find me at https://harrycochrane.substack.com/ if you would like to keep reading.

Thank you to everyone who has taken the time to follow this blog over the years. I wish that the articles had come thicker and faster. You can now find me at https://harrycochrane.substack.com/ if you would like to keep reading.

In 1895, a French composer decides to write an opera…He has already finished one opera in draft form, a three-act giant in a historical-Spanish-chivalric setting. This fulfils any lingering grand opéra responsibilities that inhabit his nationalist conscience, and he becomes unhappy with it. One night he attends a spoken play by the Belgian dramatist Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) and daringly decides to use this play as the text of an opera – without turning it into poetry, without even restructuring the sections he takes from it in any serious way, aside from some cutting and line editing. The play has only one brief passage that in any way lends itself to becoming an operatic set piece, a song for the heroine. Everything else is freeform conversation and random musing.

This is how Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker open chapter 17 (‘Turning Point’) of A History of Opera: The Last 400 Years. Immediately, we are pulled in by the paragraph’s pacing: not only is it talking about a form of drama, it is also structured like one, with questions advanced and unanswered. Who is this unnamed French composer? Why does he choose to lift a play wholesale from the page, which sounds, even to the most lay of readers, like a pretty radical thing to do. What happened next? Was it a theatrical success?

A History of Opera was lucky to be written by two academics who understand drama in practice as well as theory. Had I known what a thriller awaited me, I would have bought it one summer day in 2016 at a bookshop in St Boswells. Instead, I ordered it to Ravenna, Italy, some nine months later: in the lubricious thrall of a young relationship, I had booked two tickets to see Così fan tutte at the Teatro Alighieri, and thought that some heavily-worn knowledge could do no harm to my continued eligibility. The production itself was not exalting – I suspect that Così is not the best induction – and for my handful of nights at the opera since, I have less Mozart to thank than Abbate and Parker.

These are two people who have dedicated their lives to the art form, so we might not expect them to fully recognize, never mind revel in the absurdities of it. Yet they do. “Opera is a type of theatre in which most or all of the characters sing most or all of the time” is their opening definitional gambit – though they suggest that purely spoken theatre has, over the millennia of human civilization, been the exception rather than the rule. And as a chapter on German Singspiel highlights, it was singing most of the time, rather than all of the time, that caused the headaches, as composers contrived ways of softening the inevitably bumpy transition from speech to song.

A History of Opera is a history of tension, conflict and creative angst, though there seems to have been none on the part of the authors, whose prose styles blend fluidly and faultlessly (you can try to guess who wrote which chapters, but one instance of “pants” and another of “trousers” is really all you have to go on). There is an irony here, as operatic collaboration has rarely been a seamless enterprise. While divas and divos were making serious money – Abbate and Parker note that opera may have marked the first equal-opportunities moment in history, as far as fees were concerned – it wasn’t until the 1800s that the composer started to emerge from hired hackdom. Opera was a popular entertainment, after all, just one that somehow attracted high-art critique. “There is scarcely a decade in the eighteenth century that avoided some philosophical debate about opera’s ills – often, human nature being what it is, the ills of other people’s opera rather than one’s own.”

But though Abbate and Parker have the humour to laugh at these querelles and the prose to make us laugh with them, their book succeeds because it convinces us that all this agonizing mattered. Take Rossini, who until the late 1820s ruled the operatic world like a velveted Taylor Swift; Stendhal compared him to Napoleon. But he spent his last forty years producing nothing but genial anecdotes, a Missa solemnis and Tournedos Rossini, a recipe for fillet steak topped with foie gras and black truffle. The Rossinian brand of transportive vocal beauty, with coloratura lavished equally over all the characters at all their junctures, was blown away by a new breed of heroic tenor. Male singers in the 1830s, as the authors sartorially put it, “increasingly adopted the vocal equivalent of stovepipe hats and dark suits”, as “the centre of gravity of the Italian orchestra became lower”. In musical terms, “When this kind of tenor hits a high note – generally defined as anything higher than the A above middle C – and hits it in the chest voice…the resulting acoustic explosion is a force of nature that would come to represent overwhelming male passion.” These new vocal preferences, which saw the castrato ejected from polite society, were talismanic of a broader and deeper operatic sea-change, with the old structural forms found increasingly wanting.

Nobody, however, changed the rules of engagement more than Richard Wagner, who casts an iron shadow over the book’s latter half. Of course, the effect of Wagner’s music can only be experienced first-hand, but one cannot imagine a more exciting foreword to Tristran und Isolde:

It starts with a four-note melody played by the cellos. On the last note the cello is joined by other instruments, forming perhaps the most famous chord ever: starting from the bottom, F, B, D# and G#, scored for oboes, clarinets, cor anglais, cellos and bassoons. Ever since 1865 this collection of notes in this particular order has become instantly recognizable, peculiar and inimitable, notorious in its instability. It is dissonant and unstable, demanding resolution; but it resolves to yet another unstable chord – a more conventional dominant seventh – as if a question has been answered by another question…melodies end by beginning other melodies, harmonic resolutions are delayed or obfuscated or never arrive or are there only for an instant.

In its rolling instability, the Tristan chord offers a metaphor for the operatic terrain once Wagner had shaken it. “His operas resonated around Europe and beyond whether you shunned them or stared them in the face. They resonated even if you lampooned them”. It took something extraordinary to slip Wagner’s gravitational field; it took that young Frenchman we started with. Debussy’s Pelléas et Melisande marked an epochal heave away from many Wagnerian norms, though Debussy was not the only one doing the heaving. One critic wrote that “after listening [to Pelléas] one feels sick…one is dissolved by this music because it is in itself a form of dissolution.” Abbate and Parker: “often the characters barely intone their lines, with music so austere as to be next door to silence.” Significantly, Debussy never wrote another opera, the subtext being that work so original comes at the price of unrepeatability.

Nausea seems to have been the order of the day at the turn of the century: perhaps an audience surfeited on Wagnerian and sub-Wagnerian leitmotifs needed to purge themselves. The propulsive thrill of chapter 17 still has me searching the calendars for Richard Strauss’ Salome, another libretto taken unaltered from a prose drama. The source text this time was by Oscar Wilde, so we can blame him that “insanity and perversion are presented for viewing pleasure…in flowery phrases full of highly perfumed poetic metaphor”. As for Strauss’ music, “unsavoury characters such as Herod quaver and pipe, shriek and snarl”, while the uniquely sinless Jokanaan/John the Baptist sings from his cistern in a warm, Lutheran baritone. Salome was a high watermark in what would come to be known as “expressionism”, where the artistic toolbox works both a microscope and a megaphone of the character’s inner life. Strauss’ “frequent lingering on extreme perceptions and mental states has a shattering effect on audiences…Even today, good performances of Salome tend to be received with moments of stunned silence.” On my third and latest reading of Abbate and Parker, who have been there themselves, I still got a contact high.

For an opera newbie like me, most of these highs are still waiting to be discovered. At present, I remain as much an armchair opera-lover as I am an armchair traveller, and the fact that many others are the same need not signal a decline. On the one hand, the caverns of Youtube have recordings from the most obscure corners of the globe, opening singers and composers to a potentially vast audience. On the other hand, the torrent of production has slowed to a trickle; it was already slowing in Verdi’s time. The modern renaissances enjoyed by Handel, Rossini and Donizetti are doubtless no more than their due, but such musical archaeology speaks of a museum culture with few new exhibits.

Apart from the towering exception of Benjamin Brittan, almost no postwar works have established themselves in the repertory. But, Abbate and Parker counter, “is joining the repertory the only exam worth passing?” Theatre design encourages us to think so: large orchestras and Valkyrian voices are needed to fill the modern auditorium. Composers and directors are forced to work on grand scales, not on modest ones, so they don’t realise that modesty can be liberating. Unlike most proposed remedies, Parker and Abbate suggest that we stop worrying about popularity and staying power, and start “embracing ephemerality as a positive phenomenon”. In the seventeenth, eighteenth and much of the nineteenth century, “operas were disposable, and that very disposability was a sign of fervency and creativity.”

It’s a lesson that opera could learn from literature. A century from now, will people still be reading all, indeed any of Sally Rooney’s novels? It’s not really a question that preoccupies us, or the reviewers. Opera, maybe because of all the money and man-hours sunk into it, is fraught with anxieties of permanence. A History of Opera: The Last 400 Years has its finiteness built into the title, and never do Abbate and Parker risk any grand prognoses of the next four hundred. Nothing ages faster than a confident prediction. But I will confidently predict that the book will reel in anyone who gives it a chance, however many or however few chances they’ve given opera.

A History of Opera: The Last 400 Years is published by Penguin and is available here.

From one point of view, reviewing The Big Sleep is a bit like reviewing a Raphael Madonna, albeit with fewer virgins. Nevertheless, even the most hallowed cases can be reappraised, especially when they are so frequently and shamelessly revisited. Evaluating one author’s mistimed jump on the Chandlerwagon, Martin Amis wrote: “it is no great surprise that Perchance to Dream isn’t much good. The great surprise (for this reviewer) is that The Big Sleep isn’t much good either: it seems to have aged dramatically”.

It’s true that The Big Sleep isn’t much good as a detective novel, despite its primogenitory status in the “hard-boiled” crime genre. Chandler himself was happy to admit that he didn’t really know what happened in the end, and I’m happy to admit that I didn’t really know what was happening throughout. The characters are beautifully sketched in physical terms, especially when the physique is beautiful:

She had lovely legs. I would say that for her. They were a couple of pretty smooth citizens, she and her father.

Which shows the novel’s vein of sardonic humour: you initially think that “a couple of pretty smooth citizens” refers to her legs. Legs are something that Marlowe – Chandler’s “big dark handsome brute” of a private eye – never fails to notice, and yet for all his allure and alertness to women, there is a wounded chastity about him. He is cold-blooded not in seduction but in rejection, brutally batting away his client’s daughters with lines like “Don’t think I’m an icicle…I’m not blind or without senses. I have warm blood like the next guy. You’re easy to take – too damned easy.” Clearly, this is not an episode of Lewis.

In fiction, private dicks can always behave less ethically than their state-employed counterparts, and the “hard-boiled” genre is famous for smudging the line between the good guys and bad. In The Big Sleep, though, the hard-boiling reduces everyone to a Big Soup. However sharply Chandler draws the suits and the eyebrows, everyone – at least all the men – talk in the same underworld patois:

1. “I can believe that whatever you know about all this is under glass, or there would be a flock of johns squeaking sole leather about this dump.”

2. “Real money, they tell me. Not just a top card and a bunch of hay…His wife says he never made a nickel off old man Sternwood except room and board and a Packard 120 his wife gave him. Tie that for an ex-legger in the rich gravy.”

3. “You got the books, Joe. I got the sucker list. We ought to talk things over.”

One of these is Marlowe, one is a policeman, Captain Gregory, and one is racketeer supremo Eddie Mars. Unlikely as it may seem, The Big Sleep has us asking the (futile) question that we ask of Shakespeare: did anyone ever actually talk like this? Scorsese and De Niro are often accused of glamorizing the gangster life. Chandler glamorized the gangster lingo, writing a dictionary-defying poetic-demotic that is just that: written. It’s great, but its ubiquity does nothing for the definition of the characters amid the murk of the plot.

And to be honest, the dialogue isn’t Chandler’s true strength. It’s Marlowe the narrator who gets all the best lines, especially those that flaunt his talent for metaphor. “It was raining the next morning, a slanting grey rain like a swung curtain of crystal beads”; “The pug sidled over flatfooted and felt my pockets with care. I turned around for him like a bored beauty modelling an evening gown.” Very few sentences are allowed more than one comma: they snap shut like a loaded revolver. This, one suspects, is what has propelled The Big Sleep to the orders of “high literature”. It’s worth bearing in mind the words of Joel Cohen, who wrote The Big Lebowski by looking to Chandler’s “hopelessly complex plot that’s ultimately unimportant”.

The Big Sleep is published by Penguin and is available here.

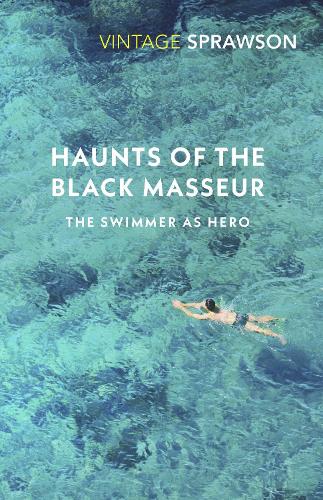

Tastes may change, but surely some things are eternal? Apparently not. Take Love, our one common bond, our human birthright (right?). A medieval fabrication, thought C. S. Lewis: no one falls in love in the Aeneid. Charles Sprawson’s Haunts of the Black Masseur does not talk about Love, but it does talk about swimming – which, one would imagine, has been practised in more or less the same way and with the same alacrity since our ancestors first grew lungs and hauled themselves ashore.

One would be wrong, though. The Romans were mad for it, as we know – “swimming was so popular that the inability of the Emperor Caligula to swim caused comment” – but throughout the Middle Ages “instances of swimming in England were rare and sporadic. Almost no one swam in the sea”. How does Sprawson know this, we might ask? We have to take him on trust as a man who, while teaching Latin in a moistureless Saudi Arabia, became “acutely sensitive to the slightest trace of water, any passing reference to swimming”. Aquatics turned into a physical and intellectual obsession, somehow not hindered by a longtime bathophobia:

My dread of deep water stems from a voyage to India at the age of six…As we rowed out from the shore across the shallow water the bottom dropped down suddenly at the edge of a steep massive cliff, and we found ourselves floating in clear smooth water over rocks rising up from an apparently unfathomable depth to quite near the surface…those submarine peaks rising abruptly from the seabed has marked my imagination for life.

Depth (my own comparably vertiginous memory would be the sight of a rusty buoy chain plunging silently into the dark of Lake Windermere) is Sprawson’s main criterion for swimmers. We learn that Shelley repeatedly courted drowning before it actually happened: according to Trelawney, he once lay “stretched out on the bottom [of the Arno] like a conger eel, not making the least effort or struggle to save himself”. Byron was the exact opposite, a supreme swimmer who showed little interest in what lay beneath the waves, but this blitheness was to his advantage when he came to cross the menacing drops of the Hellespont. For Sprawson, it all suggests “the superficiality of Byron’s imagination as well as nerve…His genius was for the surface of life.” Byron himself wrote “I plume myself on this achievement more than I could possibly do on any kind of glory, political, poetical or rhetorical”, which is consistent with his line in Beppo: “One hates an author that’s all author”.

Of these same we see several, and of others,

Men of the world, who know the world like men,

Scott, Rogers, Moore, and all the better brothers,

Who think of something else besides the pen…

Much space is also given to Algernon Charles Swinburne, who, true to type, approached swimming as an almost flagellative activity. He took “a masochist’s delight in being scraped by pebbles, pounded by waves”, needs met by the sea off Northumberland, where he spent his summer holidays. Sprawson then counter-chronologically moves to the famous opium-eater Thomas de Quincey, and draws compelling parallels between drug trips and the swimmer’s sense of temporo-spatial suspension:

Anyone who submerges some way below the surface into deep water can experience the nightmare visions of de Quincey’s…of sinking down through huge vaulted airless spaces, among rocks and columns that rise up from the ocean floor in a limitless and yet claustrophobic expansion of space, alone, but not unobserved; there is a sense that one is always under surveillance, invisible enemies and predators are somewhere hidden…the slightest touch or sound can cause alarm in this silent world.

Sadly, the rest of Haunts of the Black Masseur is not quite as interesting. From halfway onwards, we essentially tootle through the personal swimming habits of selected literary individuals – which we had also been doing previously, but which the Byronic chutzpah had kept us from noticing. A history of any commonplace pursuit is always going to struggle with the archives – in 300 millennia of homo sapiens, what percentage of human dips have been recorded in diaries and letters, never mind in canonical poems? Sprawson’s is necessarily the tip-of-the-iceberg technique. Edgar Allan Poe, Allen Tate and Mark Twain all enjoyed splashing around, so he contends that “swimming became established in the Southern imagination as a symbol of evasion, a means of refuge and withdrawal.” Whether the average Alabaman or Arkansawyer saw it like that, we can never know.

A book like this was never going to be comprehensive, but we might have wished it a little less occidental. We learn that it was the Native Americans who taught the world the front crawl/freestyle, at a time when everyone was swimming breaststroke. Otherwise, non-western traditions have to wait until the final, Japanese-focused chapter, where we are told that “Swimming was by no means an exclusively masculine pursuit” – though on page 284 out of 305, we could be forgiven for thinking it was. The women in question are the Ama, who for 2,000 years have dived off Honshu’s shores for shellfish and seaweed, going down as far as sixty feet. “Men”, Sprawson tells us, “are excluded because they could not stand the cold”. Which begs the question: if women can go deeper, why doesn’t Haunts of the Black Masseur go into depth on them?

Haunts of the Black Masseur is published by Vintage and is available here.

Anthony Horowitz’s Alex Rider series landed among the late millennials like a drop pod of Space Marines, which we were all collecting. They were, to quote Blackadder, full of capture, torture, escape, and back home in time for tea and medals. Even the cool kids at my school, the casual, uncommitted bullies, were reading Stormbreaker, Point Blanc and Scorpia; lesser spotted were the Diamond Brothers books, in which Horowitz indulges a love of classic noir and black comedy. I worked my way through the punning titles – The Falcon’s Malteser, South By South East, The French Confection – and last week I picked up The Blurred Man for the first time in twenty years, curious to see how my response at thirty differed from that at ten.

The Diamond Brothers are Tim and Nick. Tim is a very stupid private eye; Nick is a smart, smirky fourteen-year-old. They live together in London and poverty, their parents having moved to Australia. Nick is the first-person narrator of the novels, which nicely inverts the traditional pairing of genius detective/slow-witted sidekick, a generic convention that grew out of the former’s need for someone to whom they could articulate their sleuthing. The Blurred Man is a fuzzy photograph of a reclusive philanthropist called Lenny Smile, whose children’s charity, Dream Time, has received two million dollars from American crime novelist Jack Carter. Carter has arrived in London to meet his beneficiary in person; unfortunately, Smile died a few days before his arrival. And Horowitz doesn’t spare his young target audience: Smile was accidentally run over by a steamroller, which tees up a string of queasy jokes when Nick and Tim go to visit the gibbering wreck of a driver.

“It must have been a crushing experience,” Tim began.

Krishner whimpered and twisted in his chair. Dr Eams frowned at Tim, then gently took hold of Krishner’s arm. “Are you all right, Barry?” he asked. “Would you like me to get you a drink?”

“Good idea,” Tim agreed. “Why not have a squash?”

Krishner shrieked. His glasses had slipped off his nose and one of his eyes had gone bloodshot.

“Mr Diamond!” Eams was angry now. “Please could you be careful what you say. You told me you were going to ask Barry what he saw outside Lenny Smile’s house.”

“Flat,” Tim corrected him.

The humour in The Blurred Man comes from two sources, the witty Nick and the unwitting Tim, with inconsistent success. The latter is too gormless to be truly credible; as P. D. James observed, the Watson should be only slightly less intelligent than the reader. Nick, meanwhile, is constantly firing off wisecracks both as character and narrator, some of which betray a pungent nastiness: one old woman has a face “that had long ago given up trying to look human”. Considering Smile’s associates Rodney Hoover and Fiona Lee, he concludes that “they could have thrown him in front of the steamroller – but if so, why? As Tim would doubtless have said, they’d have needed a pressing reason.” That’s one of the better gags, but I have to admit that at no point, twenty years on, did I laugh out loud – though I’m pretty sure there’s at least one that I didn’t get on my first reading:

“I’m still at the Ritz,” Carter said. “Ask for Room 8.”

“I’ll ask for you,” Tim said. “But if you’re out, I suppose the room-mate will have to do.”

Then again, I never opened these books for the quips. The Diamond Brothers were responsible for putting me on the mystery trail; they were really the first whodunnits I ever encountered. And Horowitz may think kids are easily amused, but he doesn’t underestimate their grasp of human vice and venality. For British readers, a rotten charity that notionally makes children’s dreams come true has a sickly relevance. Nor, crucially, does the plot condescend to cheap tricks that any adult could see through. Readers can make up their own minds about the streak of grotesquerie, but jokes aside, The Blurred Man is a satisfying, unsaccharine little tale.

The Blurred Man was published by Walker and is available here

“Mens sana in corpore sano is a contradiction in terms”, wrote A. J. Liebling (1904-63), “the fantasy of a Mr Have-your-cake-and-eat-it”. (Liebling, the reader soon learns, always chose to eat it rather than have it). “No sane man can afford to dispense with debilitating pleasures; no ascetic can be considered reliably sane.” This is the keynote of Between Meals, the memoirs of a journalist-hedonist known mostly, if known at all, for his columns in the New Yorker.

Liebling’s Eden is 1920s Paris, but as his commentator notes, the usual suspects fail to materialize. There is no carousing with Hemingway, Stein, Fitzgerald or Joyce. The only wing he is under is that of the playwright Yves Mirande, who (if his modern unrenown is anything to go by) seems to have spent more effort on perfecting the life rather than the work. Liebling knows his mentor as a breezy womanizer, a devout Catholic and a “great round-the-clock gastronome”, but witnesses the sad decline of an eighty-year-old man who has succumbed to the advice of the “psychosomatic quacks” and gone on a diet. The problem is clear. Mirande’s organs clocked no passing of time when they were getting regular sensory nourishment, but now, condemned to the cavernous wastes of self-denial, they have gone the way of any neglected machine. From the stomach, the rot spreads outwards. “The damage was done”, tolls the chapter’s last sentence, “but it could so easily have been avoided had he been warned against the fatal trap of abstinence.”

Liebling, though, is less a priest of excess than a poet of sensual pleasure, a distinction borne out in a prose style that is usually exquisite, rarely extravagant. He is not writing foodporn for plutocrats; in fact, “a man who is rich in his adolescence is almost doomed to be a dilettante at the table”. According to Liebling, those with no economic limits will never discover the joys of offal like beef heart, and will never learn that there are other fish besides sole, turbot, salmon and trout. Liebling learned it, stretching out the two-hundred dollars that his father wired him every month. Until that great day, he would let his eye rove the wine list only as high as the Tavel (“as far as I am concerned, still the only worthy rosé”); that day arrived, he would flirt with ideas of Côte Rôtie and Chateauneuf-du-Pape.

Despite his pejorative use of it, the word “dilettante” could readily describe Liebling. He essentially remained a hack journo, and never wrote the novel that he dreamed of. But then he has a dilettante’s virtues: a skipping prose style and a diverse range of passions. The “small personal Olympus” that he put together as a child includes George Washington (Zeus), Lillian Russell (Aphrodite) and Enrico Caruso (Pan). Unfortunately, Lillian Russell becomes the poster girl for a polemic that we could have done without. Liebling rightly inveighs against the cultural pressures that urge women to thinness, but his call for the “return” of the “Russellinear woman…a form of animal life that no longer exists” leads in to one of the book’s bizarrer outbursts, made all the more uncomfortable by the seductive wit of the coinage.

His chauvinism extends also to nationhood. He is staunch on the primacy of French cooking, a culinary quilt in which he singles out Burgundian food as “a trumpeting perfection” (Lyon, only a hundred miles away, offers only “a honeyed surfeit”); and rarely has a good word to say about what any other country can serve up. As well as a dogmatist, he can also be a bore: two mid-point chapters on boxing and rowing will probably interest the boxer and the rower, but did not interest this non-practitioner of either. This probably counts as a failure for a trained copy-churning journalist, who should be able to grab any lapels, whatever the subject. If not, the dilettante is just that, without the “delight” that lurks in the etymology.

But delight there is in abundance, especially when Liebling farcically caves in and signs up to a Swiss slimming clinic. “The only sane man on the place, aside from us, was the masseur, a big Swiss named Sprüdli”:

‘And thou, eat thou this crap?’ I asked him in my imperfect but idiomatic German.

‘No,’ said Sprüdli, as he plucked my biceps like harp strings and made them snap. ‘I need my strength. I eat to home.’

‘And what has thou to home yesterday evening eaten?’

‘Blutwurst,’ he said, ‘and Leberwurst.’

I wish I hadn’t asked, but masochism feeds on itself, especially when there is nothing to eat…Once Sprüdli knew my hurt, he made a point of telling me at each visit his menu for the previous day.

After this “temporary insanity”, he goes back to preaching to the unconverted. After all, “the primary requisite for writing well about food is a good appetite”.

Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris is published by Penguin and is available here.

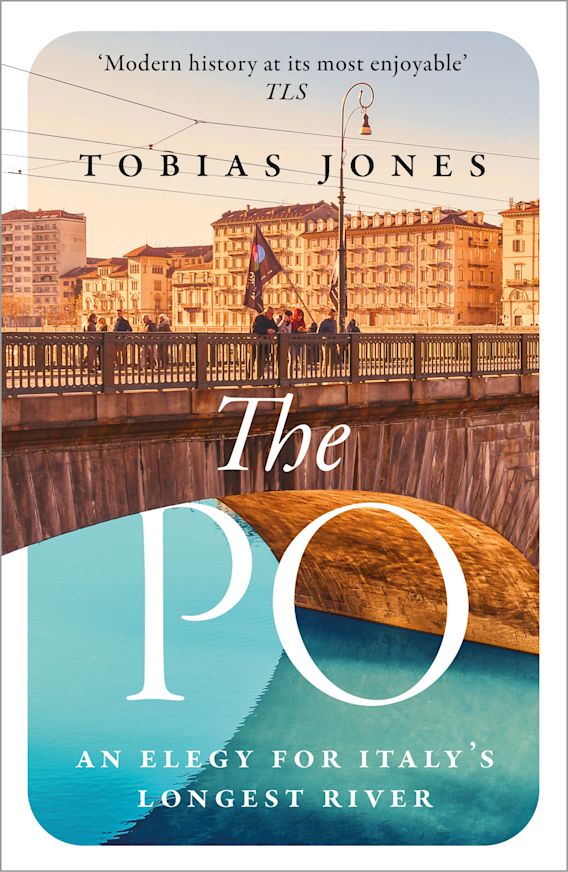

It’s curious that Italy’s longest river should have such a short name, especially in a country enamoured of long words. But then, length only says so much. Tobias Jones’ The Po: An Elegy for Italy’s Longest River is not a particularly long book, but, like its subject, it is capacious, voluminous, and sluggish. Jones starts his journey – which is literal as well as literary – in the Po delta, thence heading upstream to the source, a decision born of his professed “reluctance to go with the flow”. But he is walking, cycling, occasionally canoeing; the one who feels like they are swimming against the current is the reader.

By his own admission, Jones spends much of the trek battling with ennui in a famously, oppressively flat floodplain. “I find myself yearning for steepness”, he writes. “I’ve been tramping for months now and I’m still only about 25 metres above sea level. The river is so wide it’s unrelatable. It’s as if I’m trying to bond with a slug.” But if he can’t ‘bond’ with it, what chance have we? As someone who has lived in the fertile but deadeningly featureless Po Valley, I sympathise with the struggle while querying the premise, which obliges Jones to an exhaustive search for points of interest.

Some of them are genuinely interesting, and important. Far from cutting a groove through Padania (the etymologically-related, politically-skewed term for northern Italy), we learn that much of the Po runs high above its surroundings, corralled by a massive system of embankments which mean that “you don’t walk down to the river, but up to it”. The only proper response is a spasm of dread, historically justified by the flood of 1951: on 14th November the river started haemorrhaging at the rate of three Olympic swimming pools per second, and not until 20th December were the breaches plugged. Since then the locals have been amply revenged, with the run-off from spray-soaked arable giving us a Po ever more steroidal and choked in algae. Nobody seems to care very much. “Now the river…has no purpose for the majority of people here – it’s just an obstacle to be overcome.”

It’s that fatalist note that makes Jones’ “elegy” more like a dirge, a note that in the end subdues us to apathy. The book never really manages to bridge the gap between river and reader; we are always conscious of seeing it – picturing it, rather – at one remove. This is largely down to Jones’ encumbrant voice, which is constantly reminding us that we are in a different country and don’t speak the language, or at least not as well as he does. The old work songs of the mondine, the downtrodden rice-pickers whose tradition stretched well into the twentieth century, is imagined as “a sort of Lombardia-blues”, while “Lombardy-blues” would have had more swing, more shuffle. A fascinating observation from Fellini, who filmed in the Padanian marshes, is translated with the same tic:

We had been in Sicilia and Napoli, amidst a spectacular, Spanish sort of poverty…in the Po delta, however, the poverty had something wild, something silent. When we came across people, they displayed an Eskimo strangeness. It was as if we were on the polar ice-caps. And yet they were Italians.

Clearly, Jones’ refusal to Anglicize “Sicilia” and “Napoli” is not the main point here, but it is symptomatic of a book larded with italics, which are loudly glossed. It suffers from an Italianer-than-thou register, with Jones seemingly conversant in the many dialects that he hears along the way, and a wearying cynicism, as shown by his retelling of a riverlands folk tale: “Inevitably, they say that on moonlit nights you can still see, in the water, the white lace of her wedding veil.” Jones could hardly have written a book like The Dark Heart of Italy (2003) without a certain cynicism, but he might have dispensed with it, with that sneering “inevitably”, while paraphrasing a harmless old yarn.

Then again, months by the Po would leave anybody cynical. So many things have disappeared, be it the once-thriving sturgeon, the floating mills occasioned by the unpredictable watermark, or the river itself, branches of which now dry up completely in the summer. Jones had hoped that his journey “might be a little like being lowered into the River Jordan, the baptismal waters returning me to my place in creation. But the Po is so dirty and murky it’s as if it needs a cleansing more than we do.” With litanies of “the oily film, the plastic bags, the sewage…chlorides, phenols, phosphates, heavy metals and microplastics”, The Po: An Elegy for Italy’s Longest River is a grim diagnosis, which it should be. But it inspires less indignation than resignation.

The Po: An Elegy for Italy’s Longest River is published by Bloomsbury and is available here.

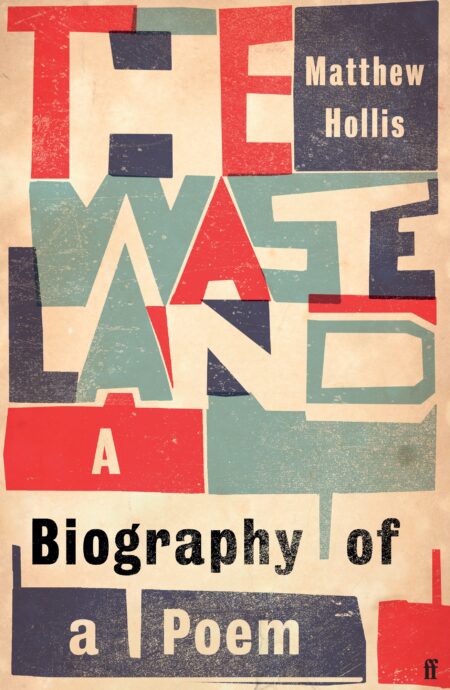

Ted Hughes said “Each year Eliot’s presence reasserts itself at a deeper level, to an audience that is surprised to find itself more chastened, more astonished, more humble”. So it’s strange to learn in The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem that Eliot’s presence was very minor indeed before the publication of the poem in question. Prufrock and Other Observations (1917) had made ripples, but Poems (1920) had sunk beneath imputations of coldness, heartlessness, and the general idea that its author was not so much a poet as a satirist. Prufrock had been published in a run of a mere 500 copies; Poems was printed by Leonard and Virginia Woolf, but in only half that number. Eliot’s greatness was hardly a foregone conclusion.

By and large, Matthew Hollis manages to recreate the uncertainty that Eliot must have felt. It would have been easy to write this ‘biography’ in the voice of hindsight, but teleological flash-forwards are few and, though we know how the story ‘ends’, we always sense that the stakes are high. The first half of the book actually has nothing directly to do with The Waste Land at all: it is as much about Ezra Pound as it is about Eliot, and as much about the reviewers as it is about the bards. Hollis brilliantly evokes the street-fight nature of publication and literary criticism, leaving us in no doubt as to the hostility that Eliot, Pound, Joyce et al. had to weather, or the independent-mindedness of the few who dared promote them. The composition of Poems, according to one review, had been time spent “very laboriously writing nothing”, while Prufrock and Other Observations met with the opinion that “erudition is one thing, the dictionary another, and poetry different from either of them”.

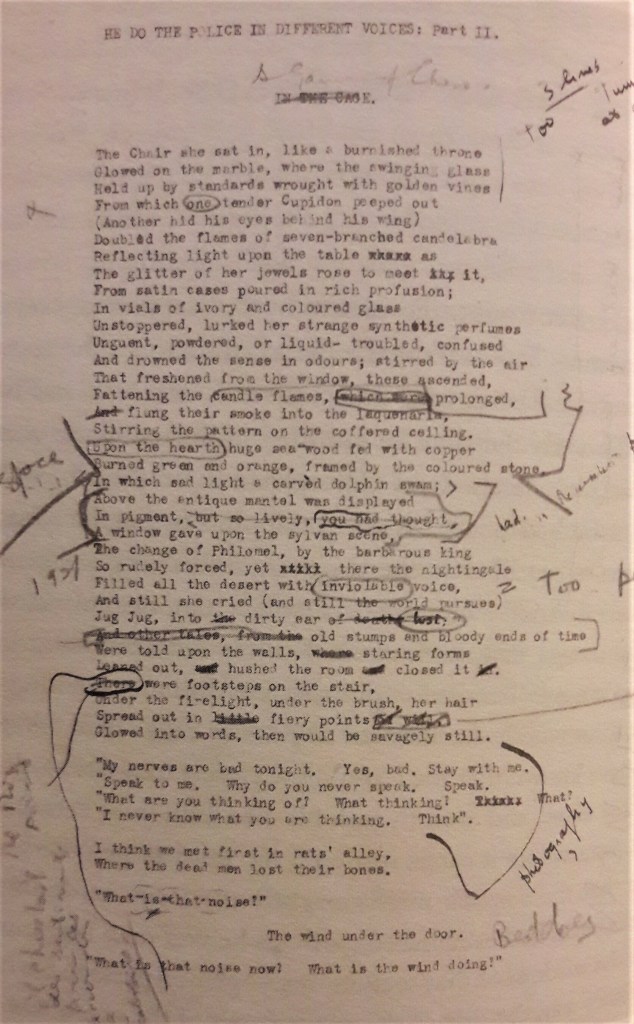

Thank God that Pound, unlike Eliot, was not easily demoralized. For Hollis, there is no overstating Pound’s role in the The Waste Land (or to use the working title provided by Dickens, He Do the Police in Different Voices), from the micro-edits to the badgering of publishers. He made good on one of his oft-quoted modernist manifestos – “To break the pentameter, that was the first heave” – and was constantly steering Eliot away from his instinctive formal purism. Part II, ‘A Game of Chess’, originally opened “The chair she sat in, like a burnished throne, / Glowed on the marble, where the swinging glass”: Pound knocked out the “swinging”, which jolted the stiff blank verse into something twitchier. He culled whole passages, such as the scatological couplets which started Part III, ‘The Fire Sermon’. He whittled down Part IV, ‘Death by Water’, to a tenth of its size, and he had the intelligence to leave Part V, ‘What the Thunder Said’, virtually untouched.

But Eliot arrived at some of the most important decisions himself. How different the first lines of the poem might have looked:

First we had a couple of feelers down at Tom’s place,

There was old Tom, boiled to the eyes, blind…

Then we had dinner in good form, and a couple of Bengal lights.

When we got into the show, up in Row A,

I tried to put my foot in the drum, and didn’t the girl squeal…

Eliot realised that this wasn’t the register he was after, and at some point – it is not quite clear when – he came up with a radical alternative:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Hollis pinpoints the crucial event: April is “not a month of growing or nourishing or nurturing as any other spring might expect, but breeding, as animals and bacteria breed.” He manages to convey the excitement of this, one of literature’s Big Bang moments, without resorting to any cheap tricks. It’s enough to know that breeding, at the end of the line, serves as a “supercharger”, one that “would fuel the early engine of the poem through a chain of reacting echoes. Breeding, mixing, stirring, covering, feeding.”

The Waste Land is often narrowly read as a symptom of a collapsing marriage, but A Biography of a Poem nuances Vivien Eliot’s reputation as a worry and a nerve-frayer. The truth is that both parties were constantly breaking down, taking it in turns to nurse each other back to precarious health; moreover, Vivien offered another sounding-board for Eliot’s draftsmanship, and her hand lives on in the finished poem. It was she, Hollis believes, who argued for Lil’s husband being “demobbed“, instead of the flabby “coming back out of the Transport Corps”. Vivien’s rehabilitation is a surprise; another is that Eliot composed straight onto a typewriter, working only from the sketchiest pencil notes. Indeed, there was little of the ‘professional’ poet about him: no real writing routine, no cave to retreat to. John Berryman summed up the Eliot phenomenon best: “he would collect himself and write a masterpiece, then relax for several years writing prose, earning a living, and so forth; then he’d collect himself and write another masterpiece, very different from the first, and so on…a pure system of spasms.”

“A system of spasms” could at times describe Hollis’ book, whose structure occasionally crosses to the wrong side of quirky. 187 pages in, we cut back several decades to Hailey, Idaho, where Pound was born in 1885; there are similar excursus on the Eliot family, one of which (admittedly early on) widens into a nine-page history of their hometown of St Louis, Missouri. These scene changes are sometimes effected with rather too much sense of their own style. A discussion of Eliot’s Poems is followed by a section break, then: “Remote, extreme, foreign: such was the mind of W. B. Yeats. Subtle, erudite, massive: that of James Joyce.” It all gets back on topic soon enough, of course – we learn that Yeats never cared for Eliot’s poetry – but in a book that is overwhelmingly both scholarly and fascinating, those adjectival triads are trying a little too hard. I would have swapped them for a bit more date-dropping, as I often found myself wondering whether it was 1920, ’21 or ’22. No doubt Hollis is keen to avoid a linear through-line that could have made The Waste Land seem inevitable, a cosy assurance that ‘he’ll make it in the end’ – he did, but Eliot couldn’t have known that for sure.

Maybe he suspected it, though. One of the most spinetingling passages in The Waste Land: A Biography is an extract from the diary of Virginia Woolf, who had failed to catch a train with the poet that she published.

‘Missing trains is awful’ I said. ‘Yes. But humiliation is the worst thing in life’ he replied. ‘Are you as full of vices as I am?’ I demanded. ‘Full. Riddled with them.’ ‘We’re not as good as Keats’ I said. ‘Yes we are’ he replied. ‘No; we dont write classics straight off as magnanimous people do.’ ‘We’re trying something harder’ he said.

The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem is published by Faber and is available here

‘This is a true story’, The Romantic all but begins. It is based, supposedly, on the incomplete biography of Cashel Greville Ross (1799-1882), which William Boyd is meant to have obtained a few years ago and which peppers the novel’s sporadic footnotes. The reader is part of a game from the outset, but one that is easily settled by a bare minimum of research. Cashel Ross did not exist; nor, probably, did ‘W.B.’ actually sign off his preface from the same city in which Joyce finished A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – ‘Trieste | February 2022’. The play’s the thing.

If Cashel had lived, he would enjoy a sizeable entry in Encyclopedia Britannica: IQ aside, he is essentially a nineteenth-century Forrest Gump. He is raised by a single mother (initially pretending to be his aunt) in County Cork. He joins up and fights at Waterloo, where he is wounded not quite in the ‘but-tocks’ but a little lower. He is cashiered for refusing to exterminate rebellious villagers in Sri Lanka, and then falls in with Byron and the Shelleys at Pisa. This is particularly tempting but always treacherous ground for a novelist, and whether Boyd has a handle on His Lordship is open to debate. His Byron has little in the way of verbal panache; in fact he reads like an insecure, intemperate bore. “[Shelley] knew that I was the greater artist. But he couldn’t live with the fact that he was inferior to me, socially speaking. In terms of rank”. This doesn’t sound much like the Byron who survives in letters and journals and anecdotes, but then Byron probably didn’t.

But if Boyd avoids the pitfalls of ham, the defining episode of Cashel’s life is a piece of Byronic plagiarism. It’s not so much that Cashel, like Byron, should fall into a passionate relationship in Ravenna – which of us hasn’t done that? – but that the relationship should be with a young, singular countess under the very roof of her weird, wizened husband. For Cashel and Contessa Raphaella Rezzo and Count Giacomo, read Byron and Contessa Teresa Gamba and Count Guiccioli. One can’t help but suspect Boyd if not of contempt, then at least an underestimation of his readers, and this shameless lifting is one of the many telltales of an author who ploughs the poppy fields of pop-lit. Being lightweight is not a crime, of course, and at least this pop sensibility lends itself to discussions of Love in all its weird, heaving brain chemistry. When Cashel meets Raphaella, “he [knows] – as an animal knows – that he had found his mate”, which doesn’t mean that Boyd will immediately give them the mind-blowing, eye-rolling sex that we think we know is coming. In fact, their first congress takes place in a cramped brougham with a servant keeping watch outside. But things get much better before they get worse, when Cashel writes Raphaella a snarling farewell and storms out of Ravenna, almost immediately starting to regret it.

We never really get to know Cashel, maybe because Boyd never tests our sympathies very far. He enjoys a good number of liaisons, as the book’s title suggests; but like Byron’s Don Juan, he is less of a great seducer than a great seducee. Claire Clairmont invites him swimming – to the outrage of a spluttering Shelley – and he accepts her further invitations on the warm sand. He is unmasked as the famous author of Nihil by a genial salonnière, and undressed: “As she had confidently predicted, [he] succumbed to Mrs Davenport early in the morning.” In New England he sleeps with the engaging Frances Broome, an apple farmer who reminds him of Raphaella; but we suppose that he wouldn’t have done so if his wife, Brìd Corcoran, had not been consumed by religious mania and ended their sexual relations. Boyd’s comment is spare to the point of perfunctory: “Cashel decided that the best and only course of action was to wait it out…He was always smiling at her, no matter what he was thinking”. The second sentence is talismanic of our mild but mildly boring hero; the first, meanwhile, is typical of Boyd’s urge to hurry things along. Pace is good, of course, but it’s the pace of a skimming stone, bouncing from place to place and rarely getting below the surface. A monkey bite in Zanzibar, for instance, sends Cashel spiralling through a handful of urgent paragraphs:

By now Cashel developed a fever, far worse than the malarial ones that he’d experienced in the expedition. He felt raging heat flaring up, in and around his body, and his bed was soon soaked in sweat. Then he began to lose track of time, not knowing whether one day or three had past, or which night he awoke, doubled up with agonizing, contorting cramps in his abdomen. His whole left leg was now discoloured, the skin hard with a dark brown crust that cracked and oozed blood when he put any weight on it. Only Kendal Black Drop provided any release or oblivion.

The prose is perfectly smooth and serviceable, oiled by pat collocations like “raging heat flaring up”, “soaked in sweat”, “lose track of time”. The narrative quality seems secondary to the action, and one fancies that Boyd is writing the source text for a film script, which is where most of his fiction ends up. Perhaps this is always a risk with the ‘life novel’, in which he has carved such a niche.

The Romantic works better when we accept that the protagonist is not Cashel but the nineteenth century itself, which develops, evolves and expands even as its journeyman remains remarkably ageless. The very title suggests that Cashel belongs to the time of the Shelleys and Byron; however well he adapts to later decades, we feel a growing nostalgia for the pre-Victorian age that we typically call ‘Romantic’. This is partly due to Boyd’s spare but convincing touches of period detail, so that we perceive a changing social timbre even without realizing it. Perhaps no surprise, then, that the final chapters should fulfil the promise of the cover image, as Cashel makes for the most romantic, cinematic, and out-of-time city of all.

The Romantic is published by Penguin and is available here.

“Terry Tice liked killing people”, begins John Banville’s nineteenth novel: “it was a matter of making things tidy…he had nothing personal against any of his targets…except insofar as they were clutter.” In a certain sense, Banville knows whereof he writes: April in Spain is a clutter-free giallo, utterly filleted of red herrings. It’s not a detective novel; it’s a crime novel, in which the characters converge on the nexus of their fates.

This is my fifth Banville but my first Banville thriller. The man himself used to be frightfully coy about his genre fiction, churning out his Quirke series, set in the 1950s, under the name of Benjamin Black (the nineteen books cited above do not include the novels on the Black list). Only recently has he acknowledged Quirke as his own, which seems like good sense – everyone knew that Black was Banville, and it’s only worth having a pseudonym if you’re going to do it properly, like Elena Ferrante.

Again, April in Spain is not a detective novel, and Quirke (we never learn his first name) is not a detective. He is the Irish state pathologist, but we meet him out of the office: his second wife Evelyn has dragged him away for a holiday in San Sebastián, which he endures with studied ill grace. Banville loses no time in flagging up Quirke’s failings. He sulks. He boozes. He asks for his steak well-done. He “enjoy[s] occasions of social awkwardness”, and expends some energy on others’ discomfiture. All this is serenely borne by the saintly Evelyn, who indulges his strops and loves him unconditionally. When Quirke finds himself in hospital – courtesy of takeaway oysters and a pair of nail scissors – he meets an Irish medic called Angela Lawless, who jogs something in his memory. Eventually he clocks that she is April Latimer, sometime tearaway friend of his daughter Phoebe. Except that April Latimer has been declared dead these four years, murdered by a mad brother.

From this point – roughly a third of the way through – Quirke ceases to be the narrative tentpole of the book and becomes one interior voice among many. The investigation falls to his daughter Phoebe, who makes the mistake of mentioning the news to April’s repulsive uncle William Latimer, Irish Secretary of Defence. Latimer extorts the help of the deviously bland Ned Gallagher, a civil servant who cannot afford to be outed from the closet, which is where he keeps all the ministers’ skeletons (and he himself has some rather more serious secrets than his sexuality). Phoebe, for her part, comes out to Spain under the protection of Detective Inspector St John Strafford, who plays the main role in Banville’s previous thriller, Snow.

Thus the narrative slinkies from one character to another, with virtually everybody getting at least one chapter except Evelyn, who remains as unknowable to her husband as she does to her reader. In fact Evelyn, who is Austrian, is the one voice on which Banville occasionally trips up: he tries to convince us that “English was the language in which she was least proficient” and makes her stumble over some unlikely words like “confound”, while not letting her miss a beat in lines like “Remember what you told me about Hemingway, that he brushed his teeth only with brandy because there were so many germs in the [Spanish] water?” More assured is Terry Tice’s geezer schtick, which goes far beyond mere patina and deep into the ventricles of his brain – indeed, as we head into the final act, it feels more like a Tice novel than a Quirke novel. On a whim, Terry buys a copy of Brighton Rock, and we follow his progress with it. “The book wasn’t bad, though he hadn’t read many books so he couldn’t really judge. The people in it were the sort he knew, though they were described in an exaggerated way. They were loud and brightly painted, like characters in a pantomime.” The literary faculty of Terry’s mind has hardly developed past childhood, hence the gauche, almost touching naiveté of his criticism. For the same reason, “the author” is never named: Graham Greene means nothing to him.

Banville has always done a good line in psychopathy (see The Book of Evidence), and Terry Tice is a psychopath who stirs both pity and queasiness. When an unwitting Phoebe spies him leaving the bookshop, he strikes her as “a sorry runt of a thing…going along at a rapid sort of strut, shoulders back and pelvis thrust forward…a not quite life-sized and in some way damaged manikin.” But if Terry is damaged, so is most of the cast. Quirke used to be a dysfunctioning alcoholic, and is now just a functioning one. Phoebe grew up believing him her uncle rather than her father. Evelyn’s family were exterminated in the Holocaust, though not even Quirke is allowed to know her parents’ names or how many siblings she lost. So the whole thing is pretty noirish, with only a light dusting of crime fiction’s campier pleasures. There’s no real sleuthing, no great moment of revelation; just the dread of the inevitable dénouement. And it’s a skill, keeping the reader hurtling towards what they know is going to happen.

April in Spain is published by Faber and is available here.